Memoir and Memory:

Elie Wiesel’s Night Trilogy

Originally Published on About.com’s Classic Literature Page

Some memoirs are remarkable because of their subject matter; some are remarkable because of how they’re written; and some are remarkable because the author has transformed extraordinary subject matter into an unforgettable literary creation, molding events into a written document that delivers the reader into the deepest heart of the author’s experience, the memoir encompassing the author, the reader, and their shared world into a common consciousness. In a more sane time than ours, Helen Keller’s The Story of My Life would have stood as the representative narrative of who we are now. Her autobiography of a self rising up out of the void of darkness and silence to reach the very heights of self-expression would have been considered our triumph as a civilization, were we actually to embody our epoch’s remarkable scientific strides forward with a correspondingly progressive human evolution. There has never been a sane time in human history, however, and, amazingly, according to statistics we are living in our least barbarous epoch yet, but the terrible truth, even in our incrementally less violent culture, is that the central event of the past century has been the Holocaust and that Elie Wiesel’s memoir Night is perhaps the one document that should be required reading for a world that wants to understand what it’s become and what it’s become capable of.

The story is now archetypal: A young Jewish boy grows up in a relatively stable family in a small town in Eastern Europe; then Germans enter the region and systematically force the Jews into cramped ghettos; truth-tellers who warn of the coming atrocities are ignored, because nobody believes that humans could be capable of such savagery; Jewish elders meet to decide what to do, and the Germans use their reluctant cooperation to manipulate the confused and fearful population; then they’re herded into trains, in ascending order of the families’ importance, to keep everyone divided and focused on preserving just themselves; rumors abound constantly: perhaps they’re being deported for their own safety, maybe even to Palestine; then they arrive at the camps, where families are separated and every individual must fight to stay alive, often at the cost of friends and loved ones, the Germans’ inhumanity quickly spawning similar inhumanity among the victims; in the end, after unspeakable abomination following unspeakable abomination, all of which Wiesel speaks of with shocking and relentless candor, almost everyone gets massacred or simply falls dead, leaving only the surviving tale-teller and a few other shattered souls piled among the corpses.

The story is archetypal, however, because of this specific book—because one exceptional mind has framed and presented the narrative in words so forged in fire that they sear into the reader to leave a permanent imprint. Wiesel’s narrative power is nearly Biblical, creating a work that has become perhaps a sacred text, a testament for a time in which humans have killed the God in their fellow humans. Part of Wiesel’s power derives from his immersion in Jewish mysticism, which he began studying just a few years before the Germans arrived. As in the other monotheisms, Jewish mysticism is esoteric to the point of being considered heretical, and it seeks to explain the eternal creative power’s relation to the temporal world in which we live. At every turn, Wiesel illustrates events using Kabalistic tales, but as the narrative progresses, the connection between our world and the divine disintegrates, and the tales stop seeming to ground the world he’s explaining and begin to undermine the sense of connection between us and any possible God. At a certain turning point, after which all vestige of humanity becomes lost, the prisoners at Auschwitz are forced to watch a young boy being hanged, his death a slow and agonizing one because his weight isn’t enough to break his neck. A man in the crowd asks, “Where is God now?,” and a voice inside the narrator replies, “Here He is—He is hanging here on this gallows.” Critic Alfred Kazin, among others, has pointed out that this death stands as a religious sacrifice, like Isaac or Jesus, and signals the literal death of God on earth.

Dovetailing with the religious influences on the narrative are the influences of existential philosophy, which Wiesel studied in Paris in the years after the war. Wiesel also studied literature, along with the Talmud, and his keen eye for the internal struggle to find and maintain meaning in a meaningless world both illuminates and darkens the text—a text that he vowed not to compose until ten years of reflection had passed. The history of the text itself—and of its tortuous path to publication—may surprise readers who take for granted its canonical existence as a seemingly uncreated and eternal testament. In 1954, Wiesel feverishly composed the first version in Yiddish, on a boat to South America, and the result was an 862-page draft that he titled And the World Remained Silent. Wiesel gave the only copy of the manuscript to a publisher named Mark Turkov, whom he met on the ship, and Turkov published a 245-page version in Buenos Aires. The book received no attention (among other reasons because Argentina was a welcoming refuge for Nazis). Then a chance meeting led French novelist François Mauriac to use his connections to push for a French translation to be published, and it took three years to find a publisher, the translation by Wiesel himself eventually whittled down to 178 pages. Another two years passed before a brave American publisher commissioned a translation, which ultimately only encompassed 116 pages. Who knows what was lost in all these translations? What’s certain is that the book as we read it is like the distilled essence of the most evil flower. It’s a razor-hewn knife that demands a blood covenant of its every reader, and it’s a knife that every generation of our civilization must continue to go under if we’re to know who we are.

But then after Night, what next? Does the narrative stop, and do we just hold this one book in place? No. The world somehow moves forward, and so does Wiesel. Since Night, Wiesel has published more than fifty books and has continued to educate and enlighten every emerging and evolving generation. Among his books, he’s written two that are thematically and perhaps spiritually entwined with Night and has bound them—both of them works of fiction that he calls “commentaries” upon the first book’s “testimony”—into the Night Trilogy.

The second book in the trilogy, the 1961 novel Dawn, features a fictional first-person narrator who finds himself and his times in a twisted dialogue with the memory of the Holocaust. The narrator, a Holocaust survivor who is now part of the Resistance fighting to establish a Jewish state in Palestine, finds the tables darkly turned, with himself now in the role of executioner. In retaliation against the British occupation, which is scheduled to execute a captured Jewish terrorist/freedom-fighter at dawn, the narrator has been ordered to execute a kidnapped English soldier named John Dawson, also at dawn. Over the ensuing night, the (significantly unnamed) narrator confronts this flesh-and-blood sacrifice, a man whose existence on earth is no mere symbol, and, even more deeply, he’s forced to confront himself, his past, and his possible future. When he pulls the trigger at dawn, following orders for his cause, he has extinguished the entire world in this one individual, just as the Nazis had done for so many millions of individual worlds in the Holocaust. He understands what has happened, but he feels that he has no power to stop it, perhaps because the Nazis have taken away his humanity and turned him into a fellow executioner. As with all the other legacies of the Holocaust that are still relevant today, the issue of victim-turned-victimizer in an endless series of retaliations continues to be a crucial one. With an apartheid Israel herding Palestinians into hot-house ghettos and refugee camps that are clearly based on the German model, and with pan-Islamic fundamentalist terror striking back at abstracted and impersonalized enemies in the West, and with those very human and very wounded enemies striking even further back into the Middle East, the drama of Dawn is unfortunately still very much in play.

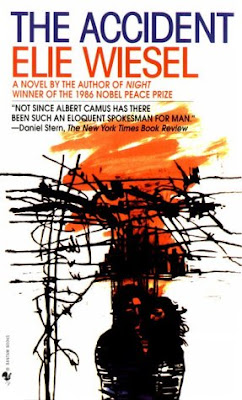

The third book in the trilogy, a novel called Day (or The Accident in some editions), takes the drama to America, where another first-person narrator struggles to maintain connection and purpose in a world where he can never feel that he belongs. Perhaps mirroring the capricious hostility of history, a speeding car smashes into the blindsided narrator, who only discovers what’s happened when he wakes up in the hospital. Lost in a floating world of pain and memory, he confronts his own inability to exist in the living thread of time, as most clearly exemplified by his tenuous relationship with his troubled but remarkable girlfriend, Kathleen. The narrator has no ability to love or to be loved, and in his disconnected confinement he feels incapable of escaping the pull of the Holocaust, which has deadened the real world for him and remains his only constant reality, this third book in the trilogy illustrating the deeply ingrained personal toll of the Holocaust on an individual who has lost his capacity for true human connection.

Not at all life-affirming in any ordinary sense, Wiesel’s Night Trilogy confronts our very worst living nightmare and reminds us that it’s a part of who we are as a species, but rather than showing us how to live with it, the way that a lesser memoir might do, it instead shows us how we actually do live with it—which is poorly. The memory of the Holocaust is a constant reminder of our worst selves, a specter haunting us as surely as death. But, significantly, neither Wiesel nor his characters let it wholly consume them. The characters in his Night Trilogy do not commit suicide, and Wiesel himself is alive to this day, working and living in the face of the blackness, a perpetual survivor whose every word and every breath is a deliberate act of moving forward with the terror. This may not be an uplifting prescription for how to live your life, but as with the knowledge of our own inevitable mortality, the ability to carry these terrible memories with us may be the only way that we can consciously choose to survive as a species.

—David Wiley