Among the most dazzling gems of American literature, Zora

Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God stands confidently in the

company of such tautly shimmering masterpieces as Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The

Scarlet Letter, Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, F.

Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts,

J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying

of Lot 49, and Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping, each of these

novels’ slim volumes serving as the receptacle of entire universes that have

been hewn with diamond-tipped virtuosity and forged into eternal works of art.

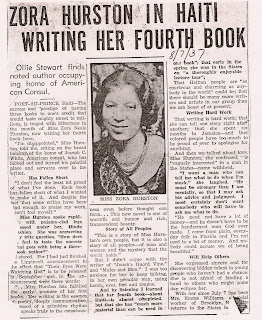

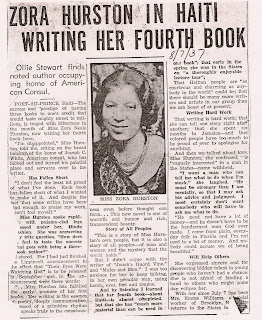

First published in 1937, Their Eyes Were Watching God

was a financial success, but it was extremely unpopular among many of Hurston’s

African-American peers. Hurston wrote the novel in what today is known as

Ebonics, and authors such as Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison lambasted it as

backwards and Uncle-Tommish, a work that they felt didn’t help African-American

writers gain any kind of serious literary voice or stature. Compounding the

issue was the fact that Hurston was an anti-integrationist Republican who was

lauded by whites who shared her beliefs, much in the same way that some of Malcolm

X’s views would later be embraced by White Supremacists. It’s possible that

today Hurston would simply be considered Afrocentric, but in her time her keen

focus on African-American culture and dialect—she was a highly educated

anthropologist and folklorist—caused her to be criticized of “ghettoizing” the

literature of a people that was desperately trying to escape marginalization.

Again, today’s

perspective might argue that rather than trying to write “protest” novels that

exposed wrongs and promoted change, she was simply portraying and celebrating a

culture that she felt was as valid and valuable and as worthy of high artistic

representation as any other. But she didn’t live in our time, of course, and

once her white admirers lost interest in her, she descended into obscurity and

eventually died penniless in 1960, to be buried in an unmarked grave and almost

totally forgotten.

Her work had

been long out of print by the time of her death, but thanks to the efforts of

Alice Walker and others in the 1970s, Hurston’s books received a second chance

at life, and since then Their Eyes Were Watching God has singled itself

out as a particularly astonishing work of art and has finally ascended to its

deserved status as one of America’s true literary masterpieces. Recently

reading this amazing book for the third time, it struck me as a strong

contender for Greatest American Novel, matching Huck Finn’s oscillating complexity and maybe even surpassing The Scarlet Letter’s magical

seamlessness.

Written

while Hurston was doing field research in Haiti, Their Eyes Were Watching

God takes place in Florida and tells the story of Janie Crawford, following

her through her childhood and through three very different marriages, from the

vantage-point of a forty-something Janie who’s telling her friend Phoeby about

her life so that Phoeby can tell the gossiping community the truth about her. Only

at times voiced in Janie’s direct speech, with Hurston very sophisticatedly refracting

most of the novel through her main character’s unique mind and history to project

an inventively original narrative language onto the page, Janie’s singular

existence strikes the reader as startlingly unique, her unforgettably distinct personality

comparable to that of Huckleberry Finn or Holden Caulfield, and her story is as

equally penetrating as the language that tells it.

|

| “Oh to be a Pear Tree,” Ann Tanksley, 2009 |

Seeing the

young Janie’s budding sexuality beginning to break loose, her grandmother

marries her off young in an attempt to give her a stable life, but the girl’s

early erotic reveries under a wild pear tree, watching the bees penetrate the

calyxes in an orgiastic swarm, permanently orient her personality so that she

yearns for both stimulation and satisfaction, leading her to follow a number of

forking paths in her attempt to get her adult self back to that wild garden. Simply

abandoning her first husband for the more ambitious Joe Starks, the still-young Janie accompanies her second husband as he lights out to found his own

mini-universe, an all-Black town called Eatonville, which was a fictionalized version of a real Eatonville in Florida that Hurston cleverly kept the name of because of its serendipitous invocation of an “Eden town.” Setting himself up as a

kind of Old Testament creator—note the ceremony that he makes when he installs

the town’s first street lamp, letting

there be light, as well as his favorite exclamation when

agitated: “I god,” rather than “my god,” as if in anger he were merely invoking

himself—he also exemplifies all of the Hebrew god’s childish narcissism,

jealously demanding more and more devotion from Janie while offering none in return,

as if doting attention were his birthright. After twenty miserable, abusive

years together, with her pedestalled position as shopgirl in Joe’s store

offering her no chance for self-expression or satisfaction, he finally dies—but

not before she finally upbraids him for “worshippin’ de works of yo’ own

hands”—and Janie suddenly finds herself financially independent and the master of

her own world, and consequently in great demand among the entire state’s

suitors, who all want to put her back in her place.

|

Michael Ealy and Halle Berry in the 2005 film

version of Their Eyes Were Watching God |

Among her more persistent romantic supplicants, pressing his cause distantly

through Janie’s friend Phoeby, is an undertaker from Sanford, but Janie tells

Phoeby that she loves her freedom too much to think about anything like that

just yet. Only one page later a younger man calling himself Tea Cake comes into

her store and wakes up her long-dormant curiosity about life, treating her as

the equal she is and rapidly opening up capacities in her that she’d never

expected to find in herself. He teaches her to play checkers, which had been

something her former husband had excluded her from, and she joyfully reflects to

herself that “Somebody wanted her to play. Somebody thought it natural for her

to play.” He teaches her to shoot a gun, and she quickly becomes a better shot

than him. Not patronizing her at all, but rather marveling at how exceptional

she is and how well matched they are, Tea Cake draws her out and shows her a

new way of life, and a new self in herself that she’d almost stopped thinking

she could ever achieve. Finally marrying for love—and also for the wild lust

that had lain long dormant inside of her—Janie embarks on a life of her own choosing.

Tea Cake is an unreliable drifter, and their relationship is far from perfect,

but their love is all the more powerful and true for its flaws and

fluctuations, and the couple gets to experience each other to the most profound

depths.

As when Huck and Jim’s boat-trip down the Mississippi takes The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn into the strangest and most relative territory, the overwhelming reality and surreality of nature suddenly heighten Their Eyes Were Watching God to a near-dreamlike state when the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane hits Florida and subjects all living beings to its mindless and merciless power. Janie and Tea Cake survive, but after a biblically freakish series of occurrences leads Tea Cake to be bitten by a rabid dog that he’s trying to protect her from during the hurricane’s hallucinatory aftermath, Janie is forced to use her recently learned handiness with a gun to shoot him in self-defense when he goes mad from contracting the disease and tries to kill her. A subsequent trial acquits her of murder, but afterward Janie is tired of life and wants to recede from it, and so she returns to Eatonville and tells Phoeby her story.

|

| Untitled, Jerry Pinkney, 1991 |

One

of the rarely discussed enigmas of Their Eyes Were Watching God is that

after Janie shoots Tea Cake, she holds him in her arms while he madly sinks his

teeth into her during his death throes. The novel never again discusses this bite, which may

or may not have transmitted the disease to Janie. Hurston cleverly arranges the

events between the bite and Janie’s resigned retirement to be almost the exact same

amount of time that it took for Tea Cake to develop symptoms, and the fact that

the novel very deliberately doesn’t address Janie’s wound anywhere in its final

pages leaves a vast ambiguity. Does Janie choose to follow Tea Cake in death?

Is this novel, a story told to Phoeby—whose name means “moon” and suggests the reflection

of light—her last testament? Or is she perhaps just telling her tale without

knowing for sure what kind of life or death awaits her after she survives these

crucial events?

Discussed even less often than this question is Hurston’s extraordinarily sly and sophisticated literary program for the novel. Using names and imagery that call up a vivid tapestry of literary and biblical associations, she asserts herself as one of the most cannily allusive of the great modernist masters. Joe Starks’ role as Old Testament deity is fairly overtly laid out, but Tea Cake’s personality and role seem so wholly and vividly original that readers can easily overlook the many layers of symbolism that Hurston builds around him. The reference that’s hiding in the plainest sight is that Tea Cake’s name is an allusion to the most famous tea cake in all of literature: the madeleine in Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. In Proust’s associative cosmos, an entire 4,000+ page novel arises from the sense memories that spring from a chance combination of dipping a madeleine cookie into a cup of tea, a blend of flavors that his narrator hadn’t tasted in decades and that resurrects in him an entire universe of lost time within his super-sensitive frame. The word “resurrects” is key to the association, because in Proust the madeleine and tea are a kind of secular Eucharist, a bread and wine that reclaim new life within the seemingly dead. With this as part of Tea Cake’s literary baggage, Hurston has him usher in a new dispensation for Janie, figuratively saving her life as he delivers her back to the lost garden and then literally saving it when he takes the dog bite that in the hurricane’s oneiric aftermath seemed to have been destined for her. While Hurston never heavy-handedly makes him into a Christ figure, making sure that he’s his own vividly original entity and that her playful allusions remain mere shading, she nevertheless uses a lot of the same imagery for him that’s typically associated with Jesus. Most notably, Hurston uses a lot of son/sun metaphors to describe him, having Janie lament after his death that “Tea Cake, son of the Evening Sun, had to die for loving her.” On the novel’s final page, after Janie ascends the steps to her old upstairs bedroom in Eatonville, she reflects, “Tea Cake, with the Sun for a shawl. Of course he wasn’t dead. He could never be dead until she herself had finished feeling and thinking.” This brilliantly subtle sun-shading suggests volumes’ worth of associative links, while still allowing the characters’ original lights to shine for themselves.

|

| “Janie and Tea Cake," relentlesscritic, 2010 |

The other

half of Tea Cake’s literary resonance arises from his other, real, name,

Vergible Woods, which he only mentions once, just before he introduces himself

to Janie as Tea Cake. Offhandedly tossing this name aside, Hurston allows the

inattentive reader to overlook it and move on, but when unpacking this

character’s many strata his true name fairly clearly asserts itself as a

reference to the beginning of the Divine

Comedy, when Vergil/Virgil arrives to help Dante out of the darkened woods,

which the pilgrim has lost his way in and is attempting to escape by trying to

follow the sun, “the planet/that leads men straight ahead on every road,” but

which he’s lost sight of because he’s looked back (as in the stories of the classical Orpheus and the Biblical Lot) and been distracted by a series of simultaneously real and

symbolized wild animals. Thus, Tea Cake is both the Virgilian guide out of the

woods and the sun toward which the lost pilgrim strives for salvation. Perhaps

he’s also even the woods itself. Tying this Dante/Virgil aspect of his name to

the Proustian aspect of his name is the scene at the end of Proust’s first

volume, Swann’s Way. Prefiguring the

fugitive years of the full novel’s subsequent half-dozen volumes, Proust’s

narrator as an old man walks through the Bois de Boulogne (the Boulogne Woods),

disgusted by the havoc that’s been done to the faces that he knew from the

past, lamenting all that’s changed and been forever lost (in Moncrieff’s

translation):

Alas! in the

acacia-avenue—the myrtle-alley—I did see some of them again, grown old, no more

now than grim spectres of what once they had been, wandering to and fro, in

desperate search of heaven knew what, through the Virgilian groves. They had

long fled, and still I stood vainly questioning the deserted paths. The sun’s

face was hidden.

This is not the blissful grove of the blessed from Book VI of Vergil’s Aeneid, but rather the sylvan nightmare that the poeticized Virgil finds the medieval Dante in (or it’s perhaps a combination of the two, since Proust

never looked anything up and often confused and conflated his remembered references),

and so with the sun’s face hidden in these Virgilian woods (dans les bosquets virgiliens, a phrase

that Hurston transforms into the name Vergible Woods), Proust and his entire

cast of characters are as lost as Dante at the beginning of the Divine Comedy, and by using just a few

brilliantly placed words and names, Hurston conjures up all these associations

as mere background coloring for a novel that’s as vibrant and complex and

original as any of the classics that exist in its wake.

A true

master, Hurston also remembers to balance all this gravity with a heaping

helping of levity, and as she opens up the novel’s field of play she repeatedly

references the greatest comic novel of them all: Don Quixote. One of Hurston’s most inspired bits is the tale of

Matt Bonner’s mule, a miniature tragicomedy about a scrawny, abused beast of

burden whose shiftless owner is Eatonville’s favorite figure of fun. Describing

the mule in much of the same language that Cervantes uses to describe Quixote’s

bony nag, Rocinante, Hurston brutalizes this poor creature and his owner with a

hilariously inspired cruelty that nearly equals Cervantes’ relentless pummeling

of Quixote and his ever-suffering steed. Perhaps, as in the case of Don Quixote, Hurston also draws

inspiration from Apuleius’ second-century novel The Metamorphoses (also known as The Golden Ass), which follows the travails of a man who’s been transformed

into a donkey and endures relentless abuse before finding salvation through the

cult of Isis. Perhaps the strangest and most inspired part of the tale of Matt

Bonner’s mule comes after the mule’s death, when a council of buzzards convenes

to discuss and devour its remains. Holding up the proceedings, the buzzards’

parson asks his congregants about the mule’s death: “What killed this man,” he intones two times,

and the chorus responds each time with the phrase, “Bare, bare fat.” What this

means is simply beyond me.

Drawing

upon another one of Cervantes’ greatest set-pieces, the brawl at the inn near

the end of the first part of Don Quixote,

Hurston has Tea Cake raise a similar ruckus at a restaurant owned by a

light-skinned black woman named Mrs. Turner, who’s been trying to lead the

light-skinned Janie away from the dark-skinned Tea Cake and toward her own brother.

Pretending to break up a fight in Mrs. Turner’s restaurant, Tea Cake in fact

precipitates a wild melee whose riotous domino effect clearly mimics

Cervantes’ brilliantly snowballing free-for-all, leaving the restaurant in a

hilarious shambles. His agitation over Mrs. Turner’s brother returns, though,

when he’s going mad from rabies and starts to fantasize that the ostensible

suitor has returned after the hurricane to lure Janie away from him. His warped

mind supposing that Janie’s been visiting Mrs. Turner’s brother when she was in

fact out trying to get medical help, he accuses her again and again, and Janie

discovers that he’s keeping a loaded pistol under his pillow. When he’s off in

the outhouse she checks and sees that three of the six chambers have bullets in

them, and so in order to give herself some warning time she spins the cylinder

so that the first three attempted shots will be harmless. Finally losing his

mind soon afterward, he aims at her and tries to shoot, the three clicks giving

her time to grab the rifle that she’d hidden in the kitchen and to shoot him in self-defense,

just as his fourth squeeze rings out, “the pistol just enough after the rifle

to seem its echo.” Having Janie kill him with this Chekhovian rifle—and with

the rising tension at each of the three clicks’ inevitable rush toward death perhaps

suggesting the three times that, as per Jesus’ prediction, the Apostle Peter denies his

master before the cock crows at dawn—Hurston ties up several of the novel’s

interlocking themes in one elegantly bloody swoop.

Burying Tea

Cake right before the novel’s end, Janie finally has her date with the

undertaker, who in lieu of having become her third husband instead prepares her

third husband for burial. It’s probably not the same undertaker as her earlier

off-stage suitor, but bringing back this sepulchral theme vividly signals

Janie’s full-circle growth between the deaths of her second and third husbands.

Ingeniously tying up these remaining thematic loose ends with Tea Cake’s

funeral—and with the lunar Phoeby set to reflect the light of the solar Tea

Cake into the future—Hurston then opens the novel’s final end completely,

leaving Janie’s ultimate fate as suggestively unresolved as any of the plots of

the century’s subsequent postmodernist novels—particularly The Crying of Lot 49, which takes this device to its logical/illogical end.

Does Tea Cake bring her death as well as life? Do we owe our sacrificing

saviors the same price that they paid for us? Is death the full consummation of

life? While Janie’s ambiguous resignation after Tea Cake’s death leaves the

novel with a universe of echoing questions, its simultaneously succinct and resonant

resolution also encloses her life on the page in a diamond-like artistic encapsulation.

Hers is a story whose brilliantly hewn facets shine on far afield of the

novel’s end, her life beyond this book’s deliberately brief 200 pages constantly

bringing us back to marvel at its seemingly miraculously composition. Likewise,

Hurston’s masterwork lives on far past the author’s decline and death and

nearly complete literary oblivion to rise up and illuminate the generations of

readers who will keep this radiant novel alive long past their own short times

on Earth, its durable pigments resurrecting itself again

and again, Phoenix-like, to live on in permanent

literary immortality.

—David Wiley