edited by Paula Geyh, Fred G. Leebron, and Andrew Levy

Originally published in The Minnesota Daily’s A&E Magazine, February 26th, 1998

Just What the Hell is Postmodernism, Anyway?

Edited by Paula Geyh,

Fred G. Leebron, and Andrew Levy

Putnam, $23.95

Although compiling an anthology of postmodern fiction seems antithetical to the

very idea of postmodernism, the folks at Norton have made a bold (if ironic and

cynical) attempt at doing just that—boldness, irony, and cynicism of course

being three prominent markers of postmodernism. Skimming the cream of half a

century of American Postmodernism, as well as including nearly a dozen essays, Postmodern

American Fiction tries to capture an aesthetic that by its very nature

eludes clear definition, as well as purports to canonize works that were

largely written against the idea of the canon. So what we have here is a

canon of the uncanonizable.

Once

you accept the premise that this anthology isn’t an absurd undertaking, the

first thing that proves you wrong is the introduction. Postmodernists generally

rail against any kind of objective authority system—especially those that fade

into the background to become implicit (see Thomas Pynchon’s 1973 novel Gravity’s

Rainbow, where the main antagonist is the sinister and ubiquitous “Them”).

And what does this anthology do? It begins with an introduction without a

byline. As if the anonymous essay were the ultimate lowdown on what

postmodernism is, not even needing to sully itself with a living, breathing

(and biased) author. It’s downright weird.

Aside

from that, it’s actually a pretty handy introduction. I guess we’re supposed to

assume that it’s written by the three editors, Paula Geyh, Fred G. Leebron, and

Andrew Levy, each focusing on his or her area of expertise. And They seem to

cover a lot of the bases. They analyze the impact of the Second World War on

literature and culture, discussing the relationship of so-called postmodernity

(a cultural term) with the emerging group of writers that critics have labeled

the postmodernists (a literary term). Also, They chart some of postmodernism’s

influences in the modernist and avant-garde artistic movements, making a

compelling and informative summary of how postmodernism evolved.

The

most interesting thing in the introduction, however, is the section headed

“Postmodern Fiction and Postmodern Theory,” which reads pretty convincingly but

ends up eroding the book’s entire authority. The discussion of

antifoundationalism begins with the statement, “If any one common thread unites

the diverse artistic and intellectual movements that constitute postmodernism,

it is the questioning of any belief system that claims universality or transcendence.”

Seems pretty accurate, but then when They go on to discuss the impossibility of

objective truth on the part of any kind of foundation, or the veracity of “the

official story,” it’s like saying “this statement is false.” Postmodern critics

are caught in a Catch-22 that nullifies any authoritative statement They could

make. And this volume just accentuates the problem.

Nevertheless,

this is a really fun anthology. They break it down into six sections of

fiction, each one exploring a particular aspect or style that (sometimes) fits

into the postmodern rubric, and one section of essays. The first section,

“Breaking the Frame,” is kicked off, natch, by Thomas Pynchon. It’s kind of a

misleading beginning, however, because while Pynchon is undoubtedly the Big

Kahuna of postmodernism, he’s hardly the first one writing in this style. Which

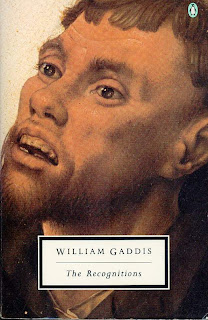

brings up the anthology’s biggest problem: There’s no William Gaddis. He’s not

even mentioned in any of the sections or in the index at the end. It’s

probably attributable to the fact that They want to make the first selection

(from Pynchon’s 1996 novel The Crying of Lot 49) jibe with Their idea

that literary postmodernism begins in the 1960s. Not True. Gaddis’ 1955 novel The

Recognitions lays the groundwork for almost everything that’s covered in

this anthology’s pages, and on top of that, it out-mind-boggles even Pynchon.

Still,

the selections here are quite good. Including folks like Donald Barthelme,

William Gass, Ishmael Reed, Carole Maso, and Lynn Tillman (Women mostly get

shunted to the end of the section! And, hey, where’s Cynthia Ozick?), They

fairly accurately cover the writers that most challenged conventional narrative

styles and forms. Although They do make the cardinal sin of referring to Gass’

story “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country” as canonical. How

unpostmodern!

The next

section, “Fact Meets Fiction,” seems a bit iffy, despite some fine selections.

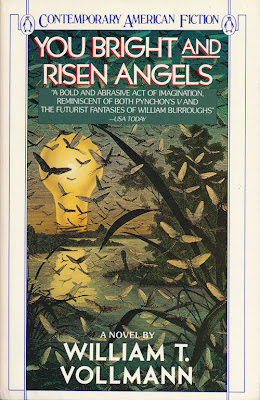

It includes William T. Vollmann, the reigning idiot-savant of American letters,

as well as Theresa Cha and Gloria Anzaldua, which are pretty great choices. But

if you want to believe that Truman Capote and Norman Mailer are postmodernists,

I guess that’s your business.

The

“Popular Culture and High Culture Collide” section would be better served by

David Foster Wallace’s wacky “Little Expressionless Animals,” which features

Pat Sajak and Alex Trebek as characters, but it’s still a good representation.

There’s Laurie Anderson (yes, the musician) and Jay Cantor and Lynda Barry

(comic book writers), as well as the obligatory Robert Coover selection.

The

“Revisiting History” and “Revisiting Tradition” sections explore alternative

versions of the past—both historical and literary. The main gripe here is that,

no matter how challenging it is, Toni Morrison’s Beloved is really more

modernist than postmodernist. Other questionable (but artistically great)

inclusions are E.L. Doctorow and Marilynne Robinson, but the John Barth, Kathy

Acker, and David Foster Wallace selections are right on, as are most of the

others.

The

“Technoculture” section might be the most interesting of the lot. Starting

things off with William Gibson and including a big chunk of Don DeLillo’s 1985

novel White Noise, this section explores the looming presence of

technology as both subject and tool of fiction. While White Noise delves

into the utter creepiness of modern technology, the J. Yellowhees Douglas and

Michael Joyce stories embrace it wholeheartedly. Unfortunately, I haven’t read

the latter selections, because they’re hypertext stories posted on Norton’s

website, and my crappy Mackintosh SE isn’t hooked up to anything except the

wall outlet (and look who’s calling other people un-postmodern!).

Despite

the sheer impossibility of its task, Postmodern American Fiction gives

an intriguing overview of what’s been happening in (and to) American literature

in this half of the century. With the “Casebook of Postmodern Theory” rounding

things out, it offers a comprehensive, if problematic, look at the radical

changes in American literature since your professors graduated from college.

Along with Gaddis’ The Recognition, this anthology works as a terrific

supplement to what you learned in your English classes. Buy them both for

yourself as your graduation presents

—David Wiley