Irresistible Grace:

James Hogg’s The Private Memoirs and

Confessions of a Justified Sinner

Originally Published on About.com’s Classic Literature Page

In an age when

Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and Hindu fundamentalists hold profound sway over

nations armed with nuclear weapons—and when many other non-religious but

nonetheless fanatically extremist ideologies threaten the world’s safety with

their urges to fulfill their purifying programs—it becomes imperative that we

examine not just the end-results of these perfectionist words made flesh (i.e.,

the Crusades, the Holocaust, Stalinism, Maoism, 9/11 and its worldwide

aftermath), but their roots in our own desires and psyches. It’s easy to point

to others and marvel at their insane beliefs and actions, but it’s only when we

interrogate our own urges to be right and to be justified (across the globe and

often beyond) that we can see ourselves as human beings with the exact same

capacity to be as misguided as the most fervent religious terrorist or the

most patriotic purveyor of state-sponsored torture.

James Hogg’s strange, terrifying,

and largely forgotten novel The Private

Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner explores the inner and outer

worlds of “justified” terror, delving into the personal terror within the most

haunted fanatic and producing a work that’s unsettling in every sense of the

word. Working contrary to many of the solid-rock beliefs portrayed within its

pages, Hogg’s novel undermines all sense of certitude and even undoes the faith

that we as readers put in its own varying and contradictory narratives.

Employing and improvising upon a host of literary conventions, devices, and

styles, Hogg’s 1824 masterpiece is thus timely to a twenty-first century

audience in both content and form and has even been cited as a forerunner of

postmodernism.

Published anonymously because of its

scandalous nature, the novel’s sections comprise a ninety-page Editor’s

Narrative, the sinner’s 140 pages of Confessions, and an additional fifteen

pages of Editor’s Narrative at the end. In the first section, an unnamed editor

reports the details of what he’s been able to gather about a strange family

history that involved a series of murders in

late-seventeenth-century/early-eighteenth-century Scotland. The opening pages

recount the marriage of the elderly Laird of Dalcastle, George Colwan (“a

droll, careless chap”), to a sternly pious young woman who tries to escape but

is returned to Colwan by her father. The unhappy match results in one

acknowledged son, also named George, and another son, Robert, who may or may

not have been fathered by the mother’s spiritual advisor, the fanatical

Reverend Robert Wringhim. Although Hogg is careful never to mention Calvinism by name, Wringhim’s beliefs make the reader infer this affiliation, and the young Robert

is raised separately from his brother, reared in an extreme version of this

faith, and is adopted by Reverend Wringhim.

|

| A brockengespenst, which may be what George sees on his hike. |

As young men, George and Robert meet

for the first time in Edinburgh and become bitter enemies, the latter soon

shadowing his popular older brother to haunt his every move. Wherever George

goes, and at whatever hour, Robert somehow takes his place next to him to taunt

him and ruin his peace of mind. The despondent George begins to fear going into

public, and after attempting to seclude himself, he makes an unplanned trek into

the hills on a beautiful morning and has a truly bizarre and ghostly

altercation with Robert that nearly results in fratricide. After a resulting

courtroom scene, George retires with friends to an inn and finds himself in a

pointless quarrel with another young nobleman named Drummond, who quickly

leaves in anger. Soon afterward, a knock on the door seems to signal his

return, and George steps out to meet him, doesn’t return, and is found dead the

next morning. Drummond flees the country and is assumed guilty, and Robert soon

afterward claims his patrimony and installs himself as the new Laird of

Dalcastle.

A complex series of investigations

follows, and through somewhat fantastical means, two women pursue a thread of

circumstances that leads them to implicate the younger Robert and a mysterious

and elusive friend who now seems to be goading him on to murder his own mother.

When officers arrive at his mansion, however, they find no trace of either Robert or

his mother, at which point the narrative reaches the end of the details passed

down about the account and then introduces the memoir left behind by Robert,

declaring that “We have heard much of the rage and fanaticism in former days,

but nothing to this.”

|

| This makes me laugh. |

Robert’s memoir—a kind of novel

within a novel—shifts the text to a radically different perspective and tells

the tale from his point of view, and true to the words that Hogg ascribes to

the novel’s “editor” (who we must remember is a character too), the “rage and

fanaticism” portrayed in his Confessions is like nothing in any known

literature, either fiction or nonfiction. As a child under the Reverend’s

tutelage, Robert learns that the Elect are pre-ordained by God and that no act

or belief can influence the spiritual fate of who does or who doesn’t go to heaven, an extreme doctrine known in Calvinism as “Irresistible Grace,” a far-flung extrapolation of Saint Augustine’s original concept of a persevering grace that keeps chosen believers from falling away from their salvation.

Exerting a wildly manipulative influence on Robert and his mother, the Reverend

struggles and prays to discover God’s will concerning Robert, and one day he

announces that it has been revealed to him that Robert is one of the Elect.

This day of revelation finds Robert at his most spiritually elated—and

relieved, as his deeply cruel and spiteful manipulations as a child and young

man have made him fear damnation—but it is also the beginning of an astonishing

and relentless descent. Seeking solitude in the woods to pray, he immediately

meets a stranger who distracts him from his task and draws him into a

theological discussion that seems to echo the Reverend’s teaching, initiating

an uneasy but unshakable association in which the stranger, whose looks keeps changing

and who only goes by the name Gil-Martin, takes the logic of Robert’s faith to

its most extreme lengths and leads him into a life of beliefs and acts that are

simply beyond belief.

Evaluating the stranger from within the frame of reference of Robert’s confessions, the reader sees that Gil-Martin is clearly the

Devil, but while Robert develops increasing fears about him as the narrative

progresses, the logic that the Elect are forever chosen and justified keeps

convincing him that Gil-Martin’s murderous suggestions are not just reasonable

but are perhaps even the will of God. Unable to elude Gil-Martin as a constant

shadow, his situation mirrors (and causes) his haunting presence by his brother

George’s side. The dual doppelganger effect becomes further accentuated when

Robert writes that even when alone he feels an uneasiness in his own skin, as

if there were a second self inside of or somehow concurrent with his own being.

Some of his language recalls the ways that Thomas De Quincey writes about his

own lack of ease with his body and mind in his famous 1821 memoir, Confessions

of an English Opium-Eater, and at one point Hogg even has Robert write a

line that directly alludes to De Quincey’s call of hope within his pain,

quoting the Psalms: “O, that I had the wings of a dove….” The self-loathing and

terror and inability to escape or transcend that Hogg portrays to such extremes

is certainly influenced by De Quincey’s language of addiction, but Robert’s

memoir takes things much farther. This is certainly no case study, but Robert’s

tortured childhood, his warped upbringing and religious indoctrination, and his

heightened capacity as an adult for unspeakable cruelty (urged on by an

inexorable outside agent) clearly illustrate Hogg’s view of how fanatical

mindsets and already unhealthy minds can combine to take a set of beliefs to

the most appalling extents, with dire consequences for everyone

involved—especially for the fanatic himself, who may in fact be the most

cruelly tortured victim.

Making his novel and its horrors all

the more ambiguous, at the end of the book Hogg has the “editor” systematically

dismantle the facts that we believed about the story and memoir and dismiss the

existence of Gil-Martin as a figment of Robert’s sick fantasy world. This

novelistic ruse may seem like a dirty trick because of its placement at the end

instead of at the beginning, but a close examination of the book’s various

parts reveals that the editor’s dismissal is far from authoritative. He claims

that all the information in the first Editor’s Narrative is based on oral tradition

and can hardly be taken seriously, but this can in no way account for the

tightly interwoven connections between the initial Editor’s Narrative and the

Confessions—connections that are so cleverly and complexly plotted that the

reader is constantly checking one against the other to piece together timelines

that add up almost seamlessly and only contradict each other in ways that their

subjective natures would be expected to do. There’s also the simple fact that

the murders and many of the other events involved police and other officials,

who surely would have left extensive records. So the book’s editor, who belongs

to a circle of writers with whom Hogg had a very uneasy relationship, makes his

own judgments on the case as suspect as those handed down through gossip.

Surely

an influence on Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, whose cyclical system

of doubles, intricate stratifications of time, and profound emotional and

physical violence forms a perfect storm of self-perpetuating terror, Hogg’s

novel also seems to anticipate the bifurcating ambiguities of Thomas Pynchon’s The

Crying of Lot 49. As in Wuthering Heights, Hogg also makes extensive

use of regional dialect, but he has much more fun with it, and despite all of

its horrors, the novel often uses its varied voices and approaches to introduce

extremely enjoyable comic relief. As in Pynchon, Hogg delights in all of his

devices, and he even makes an appearance himself at the end of the novel. Hogg

had published an article on the case in Blackwood’s Magazine the

previous year, and a section of his article is excerpted in the second Editor’s

Narrative, but when the editor goes to look for information, he runs into Hogg

at the market, where Hogg dismisses his efforts as folly and goes about his

business of trying to sell his livestock.

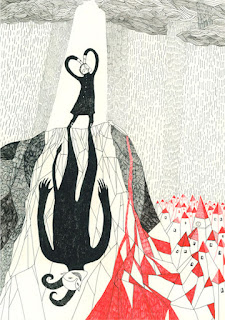

|

| An illustration from The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner |

There

are great diversions to be found in The

Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, but at its core there’s definitely not

much fun in its view of fundamentalism, and the novel’s deepest tones

are of resounding terror. Hogg was neither a psychologist nor a sociologist,

but his explorations of the profound suffering at the root of Robert’s haunted

journey give great insight into the fanatical mindset, illustrating how it can

even bring demons alive to further its mission. Although he has his editor

dismiss the memoir’s supernatural aspects, Hogg was certainly insinuating that

the Devil plays a significant role in the ostensibly holy programs of religious

mania. Whether we believe in any of this or just see it as a metaphor for madness, it’s

clear that Robert was haunted by a specter that made itself very real to him,

giving the stunned reader of this shocking novel the sense that these specters

can appear to any troubled soul of any persuasion, whether religious, ideological,

or political, and that the repercussions of following their haunted urgings can

become devastating to everyone involved when made flesh in the real world.

—David Wiley