A Review of Richard Wright’s

The Man Who Lived Underground

Originally published in the

Rain Taxi Review of Books, Fall 2021

The Man Who Lived Underground

Richard Wright

Library of America (22.95)

After publishing his 1940 novel Native Son, Richard

Wright became a literary superstar who had the freedom to pursue any inspiration

he chose. Those disparate inspirations included a photo-documentary, an

uncompleted novel about black domestic workers, and a surreal experimental

novel called The Man Who Lived Underground, which was rejected by his publishers

and which has only now appeared in its complete form.

Exploring the bizarre adventures of a black man who descends into the sewers to escape the police after he’s wrongly accused of murder, The Man Who Lived Underground is like nothing else Wright had written by then, following a dreamlike logic that reads far more like German Expressionism than like the Urban Realism of Native Son. Short excerpts of the novel appeared in 1942, and among its fans was Ralph Ellison, who ran with many of its concepts and approaches in his 1952 masterpiece Invisible Man. Disappointed by the novel’s rejection, Wright honed it into a much more effective short story that appeared in a journal in 1944, and then much later in his posthumous story collection Eight Men.

In addition to the full novel, the present volume contains the remarkable essay “Memories of my Grandmother,” in which Wright explicates what he was trying to do in The Man Who Lived Underground, while also pointing forward to his genre-defining memoir, Black Boy, which clearly grew out of this underground seam of exploration. Wright’s essay opens with this astonishing claim:

I have never written anything in my

life that stemmed more from sheer inspiration, or executed any piece of writing

in a deeper feeling of imaginative freedom, or expressed myself in a way that

flowed more naturally from my own personal background, reading, experiences,

and feelings than The Man Who Lived Underground.

This statement seems undeniably true, but that doesn’t mean that the novel works as an organic whole or that it accomplishes what Wright intended.

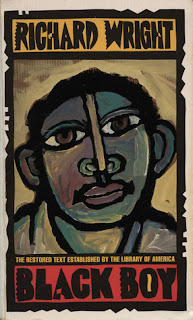

.jpg) |

| Richard Wright |

The first section

of The Man Who Lived Underground reads like hard-boiled detective pulp, appearing

to the reader to be mostly realistic and believable, with a brutal focus on the

protagonist Fred Daniels’s shocking mistreatment by the police, who extract a

false confession from him. After a weirdly unconvincing series of events, Fred escapes

into the sewers, where he almost immediately attains a detached, transcendent

viewpoint on the world and its woes. Fans of Native Son’s crystalline naturalism

would have been terribly put off to see Wright’s progressions not making

seamless sense—and not because of Fred’s trippy mental evolutions, which are

quite intriguing, but because the novel’s wild arcs don’t encompass a foundation

to support themselves.

Tunnelling through the sewers, Fred somehow scrapes his way into basement after basement, observing and judging the world’s unfortunate souls while somehow never being heard or seen. He witnesses a church choir and pities their obsequious self-denigrations; he shakes his head at a theater full of moviegoers, who he feels are just living a ghost-life and laughing at themselves; he easily finds all the tools and sustenance he needs to survive underground; and he cracks safes and breaks into jewelry shops to liberate untold riches, which in his newly alienated state he sees as entirely without intrinsic meaning or value. He plasters his cave with hundred-dollar bills, and he mashes the jewels into the ground to look like stars in the firmament, and eventually he begins to feel that he must reemerge into the world with a message for humanity—and to assume the mantle of guilt.

|

| A drawing by Franz Kafka |

Wright’s

grandson Malcolm Wright contributes an afterword to this volume, making a convincing

argument that the novel is an inverse take on Plato’s cave allegory, but the

most immediate and obvious literary influences at play here are certainly Kafka

and Dostoyevsky. The unjustly accused man (The Trial) digs into the

earth to escape his persecutors (“The Burrow”) and then goes through a series

of inner transformations that work in counterpoint to his physical degeneration

and lead to a bizarrely Christ-like apotheosis (“The Metamorphosis”). In the later

short-story version Wright goes so far as to have Fred navigate his way with

fingers that “toyed in space, like the antennae of an insect.” Likewise, the

hated man who lives beneath the world (Notes from Underground) grows to

accept and cherish his guilt and yearns to pay the consequences (Crime and

Punishment). It’s a startling literary landscape for the author of Native

Son to explore, and it would have drastically altered his own landscape—and that of his contemporaries—had he been able to make it work on the scale he envisioned.

|

| From the Invisible Man films |

—David Wiley

No comments:

Post a Comment